Malthouse presents LITTLE EMPERORS

2016 saw the glass-globe political bubble of China’s One Child Policy shatter. Picking up the pieces of what is presented as a haunted generation of youth and families, the brave new work of Lachlan Philpott and director Wang Chong is both penetrating and poignant.

A talented cast drive this absorbing story of Kaiwen (Yuchen Wang), separated from a family he is too young to remember and suddenly asked to return to the world that rejected him. His tenuous connection with his sister, Huishan, (Alice Qin) harbours a familiar Chinese communal secret, and we are plunged into a world built on memory, the subconscious and heartbreaking reality. Perhaps the most heart-wrenching character is that of their mother, played with such varied and breathtaking emotion by Diana [Xiaojie Lin] – a character so tormented by living the life she endured against her will.

Philpott’s writing is achingly familiar as it speaks to something even I, an outsider, can recognise as the universal desire for closeness with our kin. Philpott’s opportunity to visit Beijing and meet with local people whilst collaborating with Chong has given a real dimension to his work. It would be easy to dismiss Philpott’s writing as another outsider attempting to discuss the unrelatable, but Little Emperors provides a rare glimpse into a world rarely discussed or acknowledged by its own people. In the play, Kaiwen now living in Melbourne directs his own work to confront the One Child Policy, but his cast one by one vanish as they find unearthing their secrets either too painful or unspeakable.

Where this play is overall potent, the uncomfortable dialogue and acting between Kaiwen and his sound technician (Liam Maguire) distracts. While it would be easy to dismiss the relationship between these two characters, it reveals a savage loneliness of Kaiwen. This loneliness breathes throughout the play as our characters battle inner torments they find difficult to express to those around them. It is evident that those who live in Kaiwen’s originating home struggle with what occurred in their own way.

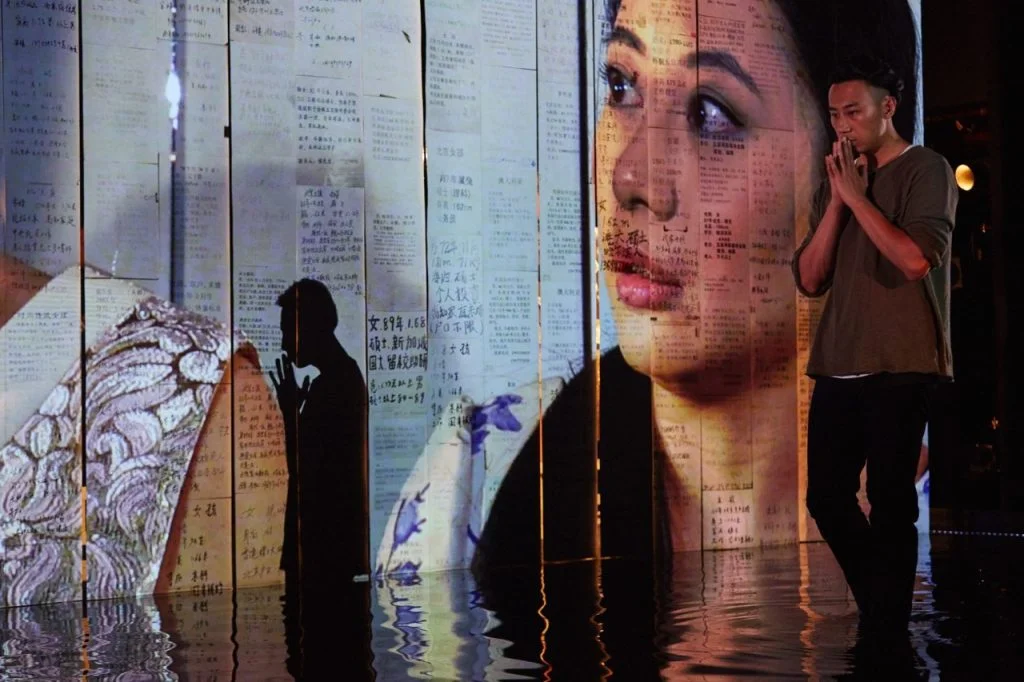

The staging of Little Emperors is visually and stylistically brilliant. The entire stage is one murky pool of water through which our characters navigate uniquely. Kaiwen walks in the water with ease, but he also uses it with a violence to convey his own turbulent mind. Little white chairs serve as stepping-stones for the women, as they, chair after chair, exhaustingly negotiate every social interaction with forced labour. In one scene, the mother beats her own body with the body of water, side to side, in an unrelenting force of self-flagellation. Romanie Harper’s set design is so effective I cannot think of a more fluid use of staging to convey the inner tumult and complexities of these characters. Nothing is left unused or unturned on the Little Emperors stage. James Paul’s sound design matches the staging with a moodiness that permeates everything around it – this little world created before us grips us in an oxymoron of vitality and gloom.

I walk out of the theatre feeling closer to a truth I heard about in passing, and I feel for a moment closer to a community I have had limited interaction with. Australian audiences can gain much by seeing this work, and it assists in breaking cultural boundaries and giving insights where none have really been offered before. This is brave, beautiful and necessary theatre.