Zoey Dawson's AUSTRALIAN REALNESS

Drawn into the notes by Zoey Dawson for her play, Australian Realness, I was captured by the unspoken truth she was prepared to tackle. Do we love the larrikin or not? Modern educated Australia says no.

It’s a depressing state of affairs, classism, and the warfare that literally ensues as this play’s absurdity evolves into an ever-fantastical barren stage of mimes. Advertised as a joke, and at times dreadfully funny, Dawson manages to spear the arts world and the educated Fitzrovians (sorry, Fitzroy bourgeoise) right in their guts. While you may at first think you’re watching a Ray Lawler play, Dawson’s distinctive touch as a playwright is her ability to coax her audience into a sense of comfort and then disrupt it with pure dystopia.

The play opens at the Christmas gathering of a thoroughly modern Melbourne family, still tepidly dipping their toes into diversity. The daughter (Emily Goddard) is both wonderful and utterly annoying as she waddles her heavily pregnant privilege across the stage, whilst her tradie partner (Chanella Macri) must politely dodge the artful Moet-filled barbs of the daughter’s mother (Linda Cropper). Greg Stone’s enthusiasm in his role as the affable father perfectly contrasts with the shrill snobbery of the mother. Janice Muller competently directs the performances in Australian Realness, which are all stellar, particularly Cropper’s transformation. I was stumped for a little while there. Who was this other actress?

A laugh here and a laugh there, and we’re taken into the underbelly of every foul assumption concocted of the working class Australian. Transformed into the bogans in the shed out back, Cropper and Stone heave with clichés. Dawson’s writing is laying it on thick here, but it achieves what it needs to. The increasingly absurdist entries of the bogan family members on stage with laugh tracks is understood to be the audience having a laugh at the working class, sit-com style. The play is totally self-aware and challenges you not to see through its display of stereotypes. Between the banker son (André De Vanny) displaying his white short-shorts whilst talking money and ordering cocaine on his 80s flip phone, and the ill-behaved bogan son playing a Bennie Hill inspired sequence with his father, we get the drift.

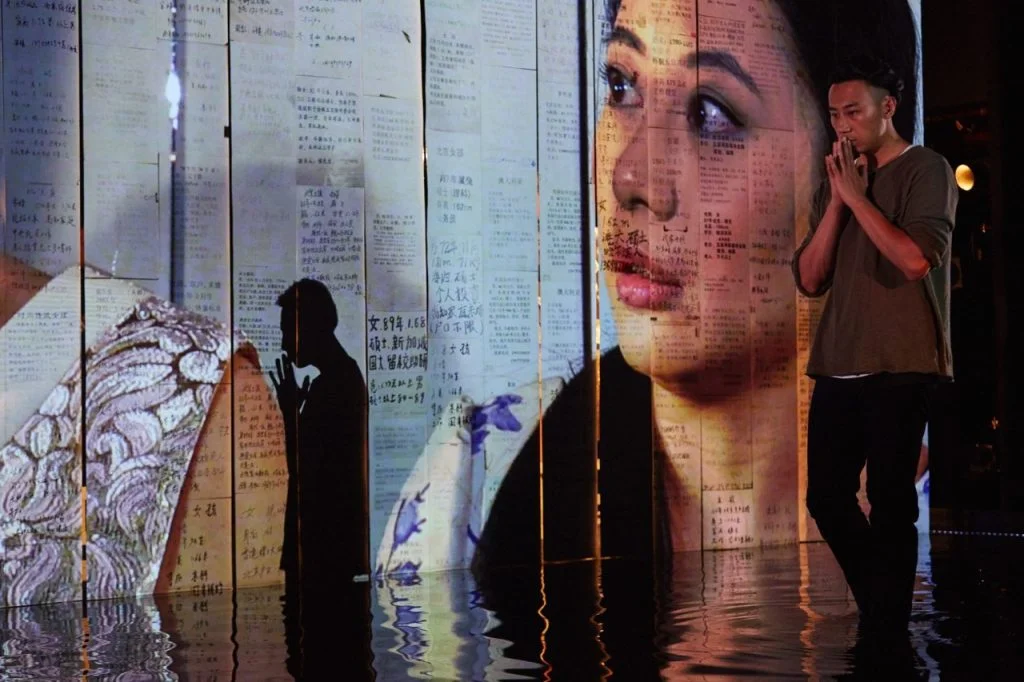

Romaine Harper’s set design brilliantly shatters itself apart from the comforts of the Aussie living room, and thrusts Goddard’s character out of her proverbial bourgeoise womb and that of her baby. The camera work from here is temporarily jarring, and we are soon confronted by the banished – a migrant woman who was once the subject of the daughter’s art. The daughter, finally levelled out by the class warfare and on the streets, confronts her new reality and rebels against it, calling the banished woman names as she hears her baby cry under the rubble, unable to accept the even playing field of this new world. Try as her character might to be magnanimous to those less fortunate, once her bubble of a life is burst, she reviles the otherness of what she once accepted from her ivory tower.

Australian Realness force-feeds the fear of the working class down the throats of educated Australia. The working class ultimately takes a wrecking ball to the art, homes and privilege of the educated. It’s almost enjoyable to see how the patronising language used by the supposedly cultured against those they exert superiority over does little to save them from their ultimate fear.

Don’t let the bastards get you down.